First-In-Human Pilot Trial for Magnetic Compression Anastomosis Device Reports Encouraging Results

Results from the first-in-human clinical trial of a magnetic compression anastomosis device known as “Magnamosis” were recently reported on in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

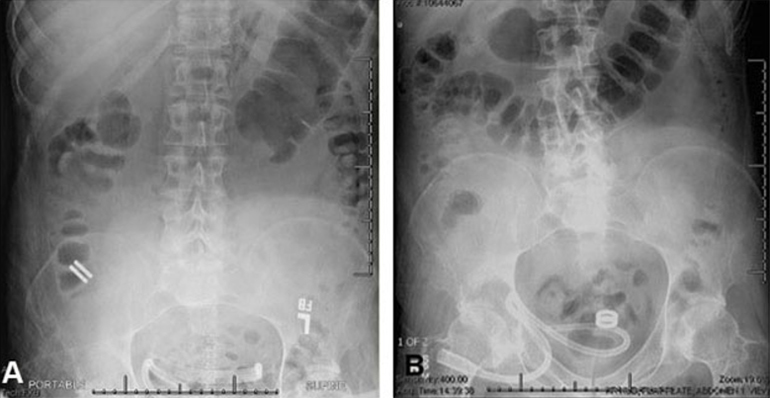

The study, led by Principal Investigator Michael Harrison, MD, is a prospective, single-center, first-in-human pilot clinical trial to evaluate the feasibility and safety of creating an intestinal anastomosis using the Magnamosis device. Magnetic compression anastomosis (magnamosis) uses a pair of self-centering magnetic "Harrison Rings" to create an intestinal anastomosis without sutures or staples. Each magnet is placed within the lumen of a desired segment of the intestine and brought together, or “mated.” The magnetic force on the compressed tissue causes necrosis and an anastomosis forms. The magnets then pass through the bowel.

Claire Graves, MD, a general surgery resident who recently completed a research fellowship in surgical innovation with Dr. Harrison, is the paper’s lead author. The paper provides historical perspective on the development of magnetic compression anastomosis against the backdrop of the traditional surgical armanentarium, sutures or staples, to create an anastomosis.

Intestinal anastomosis is fundamental to surgery. Whether repairing traumatic injury, correcting congenital anomalies, or resecting tumors, surgeons have performed this procedure for centuries. Currently, most anastomoses are either handsewn or made with staplers, but a device that could automatically and consistently produce an optimal anastomosis could reduce morbidity and save considerable operative time and resources. The concept of compression anastomosis was first credited to French physician Felix-Nicholas Denans in the early 19th century. Magnetic compression anastomosis (magnamosis) is a modern iteration of this classic idea, which uses the force of magnetic attraction to form an intestinal anastomosis without sutures or staples.

Source: Magnets-In-Me

Urological surgeons at UCSF, led by Principal Investigator Marshall Stoller, MD, performed the procedures. The urologists used bowel segments to create uretero-ileal urinary diversions, with encouraging results, according to the authors:

In this first case series of the Magnamosis device in humans, we found that despite the complicated medical conditions and comorbidities of the 5 study participants, the device safely and successfully performed in every case. No patient experienced anastomotic leak, bleeding, or stricture formation.

The authors also sketched out plans to study expanded uses for the device in subsequent patients, notably in the setting of laparoscopic surgery:

The Magnamosis device's method of slow tissue remodeling without leaving foreign bodies creates a well-formed anastomosis, which can decrease the incidence of anastomotic leaks. In addition, the simplicity of merely “sticking” the 2 segments of intestine together can save substantial operative time. However, open operation is not the best way to showcase the merits of magnamosis. In our subsequent patients, we plan to focus on laparoscopic delivery of the Magnamosis device, which currently can be deployed using laparoscopic, endoscopic, radiographic, or hybrid techniques. In addition, the device can be sized and adapted to a variety of intraluminal anastomoses, including intestinal, urologic, and biliary applications, with wide-reaching implications for the future of surgery.

Future Plans

Dr. Harrison and his research team are developing additional uses for the Magnamosis device, such as in esophageal atresia and in a novel surgical treatment for diabetes. His startup, Magnamosis, Inc., was recently awarded a NIH SBIR grant to study the effect of Magnetic Duodenal-Ileal Bypass (“DIPASS”) on Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) in rhesus monkeys.

The study team also included Ryan Hsi, MD, Catherine Co, MD, Dillon Kwiat, BS, and Jill Imamura-Ching, RN. Other contributors to the project were Dr. Shuvo Roy, Dr. Hanmin Lee, Elizabeth Gress, Stacy Kim, Dr. Luzia Toselli, Dr. Marcelo Martinez-Ferro, Dr. Stanley J. Rogers, Dr. Miles Conrad, Dr. Carter Lebares, Richard Fechter and Pamela Derish.

Related Links

Magnamosis First-in-human Study of Feasibility and Safety (Magnamosis) (Clinicaltrials.gov)

Magnetic Compression Anastomosis (Magnamosis): First-In-Human Trial (Journal of the American College of Surgeons)

Magnamosis, a New Magnetic Way to Connect Intestines, Proving Itself in Clinical Trial (Medgadget.com)